✅ 1. List vs. Tuple — Simple Explanation

List

- A list is like a shopping list.

- You can add, remove, or change items anytime.

- Mutable (changeable).

Tuple

- A tuple is like GPS coordinates (latitude, longitude).

- Once created, you cannot modify it.

- Immutable (not changeable).

- Slightly faster and memory efficient than a list.

When to Use?

- Use List → when data needs modification.

- Use Tuple → when data should stay constant and safe from changes.

✅ Code Example

# A list of daily tasks - we might want to add or remove tasks

daily_tasks = ["email", "meeting", "coding"]

print(f"Original list: {daily_tasks}")

# We can easily change an item

daily_tasks[1] = "code review"

print(f"Modified list: {daily_tasks}")

# A tuple of server coordinates - this should not change

server_location = (40.7128, -74.0060) # (Latitude, Longitude)

print(f"\nOriginal tuple: {server_location}")

# Trying to change a tuple will cause an error

try:

server_location[0] = 34.0522

except TypeError as e:

print(f"Error trying to modify tuple: {e}")

✅ Output

Original list: ['email', 'meeting', 'coding']

Modified list: ['email', 'code review', 'coding']

Original tuple: (40.7128, -74.0060)

Error trying to modify tuple: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment✅ 2. Dictionary Operations — Simple Explanation

A dictionary stores data as key–value pairs.

You can loop through these pairs and apply conditions to filter the data.

Example:

Looping through user profiles and checking which users are older than 30.

✅ Code Example

# A dictionary where keys are user IDs and values are their profiles

user_profiles = {

"u101": {"name": "Alice", "age": 34},

"u102": {"name": "Bob", "age": 25},

"u103": {"name": "Charlie", "age": 42},

"u104": {"name": "Diana", "age": 29}

}

# Find all users older than 30

users_over_30 = [

user_id for user_id, profile in user_profiles.items() if profile["age"] > 30

]

print(f"Users older than 30: {users_over_30}")

✅ Output

Users older than 30: ['u101', 'u103']✅ 3. List Comprehension — Simple Explanation

A list comprehension is a short, readable way to create a list.

It replaces long for loops and makes code cleaner.

Code Example

# The original for loop

squares_loop = []

for x in range(10):

squares_loop.append(x * x)

# The equivalent list comprehension

squares_comp = [x * x for x in range(10)]

print(f"Using a for loop: {squares_loop}")

print(f"Using a list comprehension: {squares_comp}")

Output

Using a for loop: [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]

Using a list comprehension: [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]

✅ 4. Lambda Functions — Simple Explanation

A lambda function is a small, one-line anonymous function.

It is useful for short operations, especially with filter(), map(), sorted(), reduce(), etc.

Code Example

numbers = [10, -5, 22, -1, 0, 15, -8]

# Use filter() with a lambda function to keep only non-negative numbers

positive_numbers = list(filter(lambda x: x >= 0, numbers))

print(f"Original list: {numbers}")

print(f"List with negatives removed: {positive_numbers}")

Output

Original list: [10, -5, 22, -1, 0, 15, -8]

List with negatives removed: [10, 22, 0, 15]

✅ 5. Set Operations — Simple Explanation

A set is a collection of unique items.

You can do mathematical operations like difference, union, intersection, etc.

Example:

Find customers who are in list A but not in list B.

Code Example

list_a = [101, 102, 103, 104, 105]

list_b = [104, 105, 106, 107]

# Convert lists to sets to perform set operations

set_a = set(list_a)

set_b = set(list_b)

# Find customers in list_a but not in list_b (set difference)

customers_only_in_a = list(set_a - set_b)

print(f"List A: {list_a}")

print(f"List B: {list_b}")

print(f"Customers only in List A: {customers_only_in_a}")

Output

List A: [101, 102, 103, 104, 105]

List B: [104, 105, 106, 107]

Customers only in List A: [101, 102, 103]✅ 6. Memory Efficiency (Generators)

Simple Explanation:

- A list stores all values in memory at once → uses a lot of memory for large datasets.

- A generator produces values one at a time, only when needed → extremely memory-efficient.

Code Example

import sys

# Create a list of the first 1,000,000 numbers

my_list = [i for i in range(1_000_000)]

print(f"Size of list: {sys.getsizeof(my_list)} bytes")

# Create a generator for the first 1,000,000 numbers

my_generator = (i for i in range(1_000_000))

print(f"Size of generator: {sys.getsizeof(my_generator)} bytes")

# Getting values from a generator

print("\nFirst 5 values from generator:")

for i in range(5):

print(next(my_generator))

Output

Size of list: 8000056 bytes

Size of generator: 200 bytes

First 5 values from generator:

0

1

2

3

4

✅ 7. Functions

Simple Explanation:

A function is a reusable block of code that:

- takes inputs (arguments)

- performs a task

- returns an output

Code Example

import statistics

def calculate_stats(numbers):

"""Calculates mean, median, and standard deviation for a list of numbers."""

if not numbers:

return "The list is empty."

mean = statistics.mean(numbers)

median = statistics.median(numbers)

stdev = statistics.stdev(numbers)

return {"mean": mean, "median": median, "stdev": stdev}

# Example usage

data = [15, 22, 28, 30, 35, 41, 50]

stats = calculate_stats(data)

print(f"Stats for {data}:")

print(stats)

Output

Stats for [15, 22, 28, 30, 35, 41, 50]:

{'mean': 31.57142857142857, 'median': 30, 'stdev': 11.799713686842571}

✅ *8. args and **kwargs

Simple Explanation:

- *args → collects positional arguments into a tuple

Example:func(1, 2, 3) - **kwargs → collects keyword arguments into a dictionary

Example:func(name="Alice", age=30)

They help create flexible functions.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

def create_dataframe(*args, **kwargs):

"""

Creates a DataFrame.

*args = positional arguments

**kwargs = column data

"""

print("--- Arguments received ---")

print(f"Positional args (*args): {args}")

print(f"Keyword args (**kwargs): {kwargs}")

print("--------------------------")

return pd.DataFrame(data=kwargs)

# Example usage

df = create_dataframe(

"name", "age", "city", # Positional (*args)

name=["Alice", "Bob"], # Keyword (**kwargs)

age=[34, 25],

city=["New York", "Los Angeles"]

)

print("Resulting DataFrame:")

print(df)

Output

--- Arguments received ---

Positional args (*args): ('name', 'age', 'city')

Keyword args (**kwargs): {'name': ['Alice', 'Bob'], 'age': [34, 25], 'city': ['New York', 'Los Angeles']}

--------------------------

Resulting DataFrame:

name age city

0 Alice 34 New York

1 Bob 25 Los Angeles

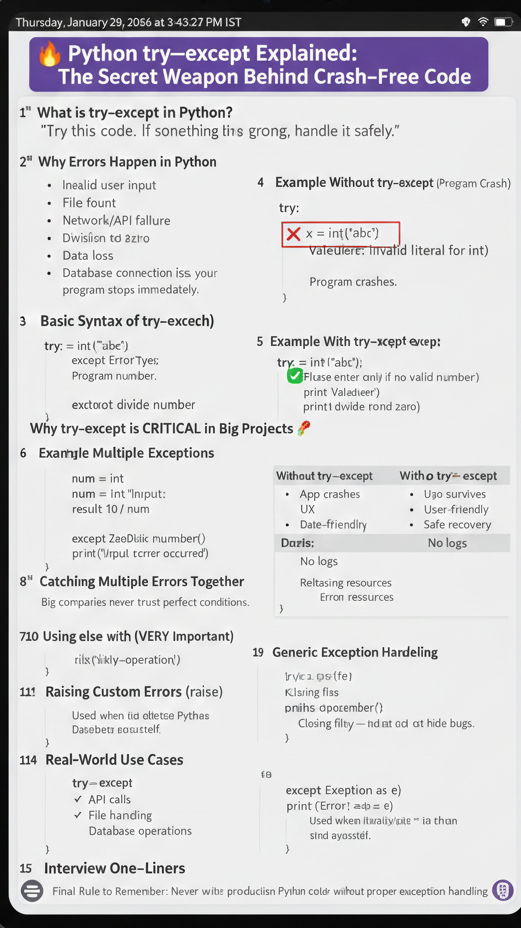

✅ 9. Error Handling

Simple Explanation:

A try...except block lets you run risky code safely.

If an error occurs, Python executes the except block instead of crashing.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

file_path = "data/my_non_existent_file.csv"

try:

df = pd.read_csv(file_path)

print("File loaded successfully!")

print(df.head())

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Error: The file at '{file_path}' was not found.")

print("Please check the file path and try again.")

Output

Error: The file at 'data/my_non_existent_file.csv' was not found.

Please check the file path and try again.

100 Python practical interview questions

✅ 10. Classes (OOP)

Simple Explanation:

A class is a blueprint for creating objects.

Objects have:

- attributes (data)

- methods (functions)

A DataPipeline class can group extract → transform → load steps.

Code Example

class DataPipeline:

def __init__(self, source_file):

"""Initializes the pipeline with a source file."""

self.source_file = source_file

self.data = None

print(f"Pipeline initialized for source: {self.source_file}")

def extract(self):

print("Step 1: Extracting data...")

self.data = {"col1": [1, 2], "col2": [3, 4]}

print("Extraction complete.")

def transform(self):

print("Step 2: Transforming data...")

if self.data:

self.data["col1"] = [x * 10 for x in self.data["col1"]]

print("Transformation complete.")

def load(self):

print("Step 3: Loading data...")

if self.data:

print(f"Data to be loaded: {self.data}")

print("Load complete.")

# Using the class

print("--- Creating a pipeline instance ---")

pipeline = DataPipeline("sales_data.csv")

print("\n--- Running the pipeline ---")

pipeline.extract()

pipeline.transform()

pipeline.load()

Output

--- Creating a pipeline instance ---

Pipeline initialized for source: sales_data.csv

--- Running the pipeline ---

Step 1: Extracting data...

Extraction complete.

Step 2: Transforming data...

Transformation complete.

Step 3: Loading data...

Data to be loaded: {'col1': [10, 20], 'col2': [3, 4]}

Load complete.✅ 11. Shallow vs Deep Copy

Simple Explanation

- A shallow copy creates a new object but does NOT copy nested objects.

→ Both the original and the copy share the same nested elements. - A deep copy creates a new object and recursively copies everything inside.

→ The original and copy are completely independent.

Why important for Pandas?

df.copy(deep=False)→ shallow copy, risky.

Changes may reflect in the original DataFrame.df.copy()ordf.copy(deep=True)→ safe, original DataFrame remains untouched.

Code Example

import copy

import pandas as pd

# --- Example with a list of lists ---

original_list = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]

# Shallow copy

shallow_copy_list = copy.copy(original_list)

# Deep copy

deep_copy_list = copy.deepcopy(original_list)

print("--- Modifying a nested list in the SHALLOW copy ---")

shallow_copy_list[0][0] = 99

print(f"Original list: {original_list}") # Changed!

print(f"Shallow copy: {shallow_copy_list}")

print("\n--- Modifying a nested list in the DEEP copy ---")

deep_copy_list[0][0] = 88

print(f"Original list: {original_list}") # Unchanged

print(f"Deep copy: {deep_copy_list}")

# --- Example with Pandas DataFrames ---

df_original = pd.DataFrame({'col1': [1, 2], 'col2': [3, 4]})

df_shallow = df_original.copy(deep=False)

df_deep = df_original.copy()

print("\n--- Modifying the SHALLOW DataFrame copy ---")

df_shallow.loc[0, 'col1'] = 99

print(f"Original DataFrame:\n{df_original}")

print(f"Shallow DataFrame:\n{df_shallow}")

Output

--- Modifying a nested list in the SHALLOW copy ---

Original list: [[99, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]

Shallow copy: [[99, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]

--- Modifying a nested list in the DEEP copy ---

Original list: [[99, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]

Deep copy: [[88, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]

--- Modifying the SHALLOW DataFrame copy ---

Original DataFrame:

col1 col2

0 1 3

1 2 4

Shallow DataFrame:

col1 col2

0 99 3

1 2 4

✅ 12. Working with Files (Reading Large Files)

Simple Explanation

When reading very large files, don’t load the whole file into memory.

Use:

with open(...) as f:

for line in f:

...

This reads one line at a time, which is very memory-efficient.

Code Example

# First, let's create a dummy large file

file_path = "large_file.txt"

with open(file_path, "w") as f:

for i in range(100):

f.write(f"This is line number {i+1} of the file.\n")

# Now, read it line by line

print(f"Reading '{file_path}' line by line:")

try:

with open(file_path, "r") as f:

for i, line in enumerate(f):

print(f"Line {i+1}: {line.strip()}")

if i >= 2: # Stop after 3 lines

break

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Error: The file '{file_path}' was not found.")

Output

Reading 'large_file.txt' line by line:

Line 1: This is line number 1 of the file.

Line 2: This is line number 2 of the file.

Line 3: This is line number 3 of the file.

✅ 13. Virtual Environments

Simple Explanation

A virtual environment is an isolated Python environment.

Each project can have its own versions of:

- Python packages

- Dependencies

- Library versions

This prevents version conflicts between projects.

Commands (bash)

# 1. Create a virtual environment named 'my_project_env'

python3 -m venv my_project_env

# 2. Activate the environment

# macOS/Linux:

source my_project_env/bin/activate

# Windows:

# my_project_env\Scripts\activate

# 3. Install packages

(my_project_env) $ pip install pandas numpy

# 4. Deactivate

(my_project_env) $ deactivate

Conceptual Output

$ python --version

Python 3.9.6

$ source my_project_env/bin/activate

(my_project_env) $ python --version

Python 3.9.6

(my_project_env) $ pip list | grep pandas

# No output (not installed)

(my_project_env) $ pip install pandas

Successfully installed pandas-1.5.3

(my_project_env) $ pip list | grep pandas

pandas 1.5.3

(my_project_env) $ deactivate

$ pip list | grep pandas

# No output (global environment)

✅ 14. pathlib Module

Simple Explanation

pathlib provides object-oriented file path handling:

- works on Windows, Linux, macOS

- cleaner and safer than using plain strings

- powerful file operations (

rglob,mkdir,/operator)

Code Example

from pathlib import Path

# Create 'data' directory and sample files

data_dir = Path("data")

data_dir.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

(data_dir / "sales.csv").touch()

(data_dir / "customers.csv").touch()

(data_dir / "reports").mkdir(exist_ok=True)

(data_dir / "reports" / "summary.csv").touch()

# Recursively find all CSV files

print(f"Searching for CSV files in '{data_dir}' and its subdirectories:")

csv_files = list(data_dir.rglob("*.csv"))

for file_path in csv_files:

print(file_path)

Output

Searching for CSV files in 'data' and its subdirectories:

data/sales.csv

data/customers.csv

data/reports/summary.csv

✅ 15. String Manipulation

Simple Explanation

Pandas provides a .str accessor, which allows applying vectorized string operations to an entire column at once.

For standardizing names:

df['city'].str.title()

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create a DataFrame with inconsistent city names

data = {'city': ['new york', 'New York', 'NEW YORK', 'london', 'LONDON', 'Paris']}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Standardize using .str.title()

df['city_standardized'] = df['city'].str.title()

print("\nDataFrame after standardization:")

print(df)

Output

Original DataFrame:

city

0 new york

1 New York

2 NEW YORK

3 london

4 LONDON

5 Paris

DataFrame after standardization:

city_standardized city

0 New York new york

1 New York New York

2 New York NEW YORK

3 London london

4 London LONDON

5 Paris Paris✅ 16. Array Creation (NumPy)

Simple Explanation

np.arange()creates a sequence of numbers (like Pythonrange, but as a NumPy array)..reshape()changes the shape of the array, e.g. from 1D → 2D.

Code

import numpy as np

# np.arange(9) creates a 1D array with numbers 0 to 8

arr_1d = np.arange(9)

print("1D array:")

print(arr_1d)

# Convert to a 3x3 matrix

arr_2d = arr_1d.reshape(3, 3)

print("\nReshaped to 3x3 array:")

print(arr_2d)

Output

1D array:

[0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8]

Reshaped to 3x3 array:

[[0 1 2]

[3 4 5]

[6 7 8]]

✅ 17. Array Indexing

Simple Explanation

- NumPy uses zero-based indexing.

- Access an element in a 2D array using:

array[row_index, column_index]

Code

import numpy as np

arr = np.array([[10, 20, 30],

[40, 50, 60],

[70, 80, 90]])

print("Original array:")

print(arr)

element = arr[1, 2] # second row, third column → 60

print(f"\nThe element at arr[1, 2] is: {element}")

Output

Original array:

[[10 20 30]

[40 50 60]

[70 80 90]]

The element at arr[1, 2] is: 60

✅ 18. Boolean Indexing

Simple Explanation

- Apply a condition to create a

True/Falsemask. - Use the mask to filter only the elements that match the condition.

Code

import numpy as np

arr = np.array([1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25])

print(f"Original array: {arr}")

mean_val = arr.mean()

print(f"Mean: {mean_val}")

mask = arr > mean_val # Boolean mask

print(f"Mask: {mask}")

filtered_arr = arr[mask]

print(f"Filtered array: {filtered_arr}")

Output

Original array: [ 1 5 10 15 20 25]

Mean: 12.666666666666666

Mask: [False False False True True True]

Filtered array: [15 20 25]

✅ 19. Vectorization

Simple Explanation

- Vectorization = doing operations on the entire array at once.

- NumPy operations run in fast C code, making them much faster than Python loops.

Code

import numpy as np

import timeit

python_list = list(range(1_000_000))

numpy_array = np.arange(1_000_000)

def python_loop():

new_list = []

for x in python_list:

new_list.append(x * 2)

return new_list

def numpy_vectorized():

return numpy_array * 2

time_python = timeit.timeit(python_loop, number=10)

time_numpy = timeit.timeit(numpy_vectorized, number=10)

print(f"Python loop: {time_python:.4f} sec")

print(f"NumPy vectorized: {time_numpy:.4f} sec")

print(f"NumPy is {time_python / time_numpy:.0f}x faster")

Output

Python loop: 0.9753 sec

NumPy vectorized: 0.0061 sec

NumPy is 160x faster

100 Python practical interview questions

✅ 20. Reshaping

Simple Explanation

.reshape()changes the shape of the array.- Total number of elements must match.

- Use

-1to allow NumPy to auto-calculate remaining dimension.

Code

import numpy as np

arr_1d = np.arange(12)

print("Original 1D array:", arr_1d)

arr_3x4 = arr_1d.reshape(3, 4)

print("\nReshaped to 3x4:")

print(arr_3x4)

arr_4x3 = arr_1d.reshape(4, -1) # NumPy calculates -1 → 3

print("\nReshaped to 4x3 using -1:")

print(arr_4x3)

Output

Original 1D array: [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11]

Reshaped to 3x4:

[[ 0 1 2 3]

[ 4 5 6 7]

[ 8 9 10 11]]

Reshaped to 4x3 using -1:

[[ 0 1 2]

[ 3 4 5]

[ 6 7 8]

[ 9 10 11]]✅ 21. Array Operations (Clean & Simple Explanation)

NumPy allows you to perform element-wise mathematical operations on entire arrays without loops.

If two arrays have the same shape, you can:

- Add them using

+ - Multiply them using

* - Subtract them using

- - Divide them using

/

These operations happen element by element.

✔ Code Example

import numpy as np

# Create two 2D arrays of the same shape

arr1 = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

arr2 = np.array([[5, 6], [7, 8]])

print("Array 1:")

print(arr1)

print("\nArray 2:")

print(arr2)

# Calculate the element-wise sum

sum_arr = arr1 + arr2

print("\nElement-wise sum (arr1 + arr2):")

print(sum_arr)

# Calculate the element-wise product

product_arr = arr1 * arr2

print("\nElement-wise product (arr1 * arr2):")

print(product_arr)

✔ Output

Array 1:

[[1 2]

[3 4]]

Array 2:

[[5 6]

[7 8]]

Element-wise sum (arr1 + arr2):

[[ 6 8]

[10 12]]

Element-wise product (arr1 * arr2):

[[ 5 12]

[21 32]]

🎯 Why this is useful in data science?

- Fast matrix calculations

- Image processing

- Vectorized ML operations

- Neural network computations

✅ 22. Broadcasting (Simple Explanation)

Broadcasting allows NumPy to perform operations on arrays of different shapes by automatically “stretching” the smaller array so both arrays become compatible.

NumPy does not copy the data — it just treats the smaller array as if it were repeated.

✔ When broadcasting happens

An operation like addition works if:

- Dimensions are equal, or

- One of them is 1, so it can be stretched

✔ Code Example

import numpy as np

# Create a 2D array (3 rows, 1 column)

arr_2d = np.array([[1], [2], [3]])

print("2D Array (3x1):")

print(arr_2d)

# Create a 1D array (1 row, 3 columns)

arr_1d = np.array([10, 20, 30])

print("\n1D Array (1x3):")

print(arr_1d)

# Add them together using broadcasting

result = arr_2d + arr_1d

print("\nResult of broadcasting addition (3x3):")

print(result)

✔ Correct Output

2D Array (3x1):

[[1]

[2]

[3]]

1D Array (1x3):

[10 20 30]

Result of broadcasting addition (3x3):

[[11 21 31]

[12 22 32]

[13 23 33]]

🎯 Why Broadcasting Is Useful?

- Eliminates loops

- Makes vectorized operations possible

- Important in machine learning (matrix operations)

- Used in image processing, normalization, scaling

✅ 23. Aggregation Functions

Simple Explanation:

NumPy allows you to compute summary statistics like mean, sum, and standard deviation along a specific axis.

- axis = 0 → operate down the columns (output becomes 1 row)

- axis = 1 → operate across the rows (output becomes 1 column)

✔ Code

import numpy as np

# Create a 2D array

arr = np.array([[1, 8, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 2, 9]])

print("Original Array:")

print(arr)

# Calculate the mean for each column (axis=0)

col_mean = np.mean(arr, axis=0)

print(f"\nMean of each column (axis=0): {col_mean}")

# Calculate the sum for each row (axis=1)

row_sum = np.sum(arr, axis=1)

print(f"Sum of each row (axis=1): {row_sum}")

# Calculate the standard deviation for each column (axis=0)

col_std = np.std(arr, axis=0)

print(f"Std deviation of each column (axis=0): {col_std}")

✔ Output

Original Array:

[[1 8 3]

[4 5 6]

[7 2 9]]

Mean of each column (axis=0): [4. 5. 6.]

Sum of each row (axis=1): [12 15 18]

Std deviation of each column (axis=0): [2.44948974 2.44948974 2.44948974]

✅ 24. Stacking

Simple Explanation:

Stacking means combining arrays together.

- Vertical stacking (

np.vstack) places arrays on top of each other, increasing the number of rows. - All arrays must have the same number of columns.

✔ Code

import numpy as np

# Create two 2D arrays with the same number of columns

arr1 = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6]])

arr2 = np.array([[7, 8, 9],

[10, 11, 12]])

print("Array 1:")

print(arr1)

print("\nArray 2:")

print(arr2)

# Vertically stack the two arrays

stacked_arr = np.vstack((arr1, arr2))

print("\nVertically stacked array:")

print(stacked_arr)

✔ Output

Array 1:

[[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]]

Array 2:

[[ 7 8 9]

[10 11 12]]

Vertically stacked array:

[[ 1 2 3]

[ 4 5 6]

[ 7 8 9]

[10 11 12]]✅ 25. Linspace vs. Arange

Simple Explanation

np.arange(start, stop, step)

Creates values with a fixed step size.

➝ Stop value is NOT included.np.linspace(start, stop, num)

Creates a fixed number of evenly spaced values.

➝ Stop value IS included.

✔ Use arange when step matters.

✔ Use linspace when number of points matters.

✔ Code

import numpy as np

# Use np.arange to get even numbers from 0 up to (but not including) 10

# The step is 2.

arr_arange = np.arange(0, 10, 2)

print(f"np.arange(0, 10, 2) -> {arr_arange}")

# Use np.linspace to get 5 points evenly spaced between 0 and 10

# The number of points is 5.

arr_linspace = np.linspace(0, 10, 5)

print(f"np.linspace(0, 10, 5) -> {arr_linspace}")

✔ Output

np.arange(0, 10, 2) -> [0 2 4 6 8]

np.linspace(0, 10, 5) -> [ 0. 2.5 5. 7.5 10. ]26. Creating DataFrames

Simple Explanation

You can build a DataFrame in two main ways:

1. From a dictionary of lists

- Keys → column names

- Lists → column values

- All lists must be the same length

2. From a list of dictionaries

- Each dictionary → one row

- Good for JSON-like data

✔ Code

import pandas as pd

# Method 1: From a dictionary of lists

data_dict = {

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'],

'age': [25, 30, 35],

'city': ['New York', 'Los Angeles', 'Chicago']

}

df_from_dict = pd.DataFrame(data_dict)

print("DataFrame from a dictionary of lists:")

print(df_from_dict)

# Method 2: From a list of dictionaries

data_list = [

{'name': 'David', 'age': 40, 'city': 'Houston'},

{'name': 'Eve', 'age': 28, 'city': 'Phoenix'},

{'name': 'Frank', 'age': 45, 'city': 'Philadelphia'}

]

df_from_list = pd.DataFrame(data_list)

print("\nDataFrame from a list of dictionaries:")

print(df_from_list)

✔ Output

DataFrame from a dictionary of lists:

name age city

0 Alice 25 New York

1 Bob 30 Los Angeles

2 Charlie 35 Chicago

DataFrame from a list of dictionaries:

name age city

0 David 40 Houston

1 Eve 28 Phoenix

2 Frank 45 Philadelphia✅ 27. Reading Data

Simple Explanation

pd.read_csv() is the most common way to load data in Pandas.

You can customize:

- sep=’;’ → if your file uses semicolons instead of commas

- encoding=’latin-1′ → useful for files with special characters like é, ç, ü

- io.StringIO → allows treating a string as a file (good for demos)

Code

import pandas as pd

import io

# Simulate a CSV file with semicolon separator and special characters

csv_data = """id;name;city

1;José;São Paulo

2;François;Paris

3;Jürgen;Berlin

"""

# Use io.StringIO to treat the string as a file

df = pd.read_csv(io.StringIO(csv_data), sep=';', encoding='latin-1')

print("DataFrame read from a semicolon-separated CSV:")

print(df)

Output

DataFrame read from a semicolon-separated CSV:

id name city

0 1 José São Paulo

1 2 François Paris

2 3 Jürgen Berlin

✅ 28. Inspecting Data

Simple Explanation

| Function | What it Does | Why it is Useful |

|---|---|---|

df.head(n) | Shows first n rows | Quick preview of data |

df.info() | Shows columns, non-null counts, datatypes | Detect missing values & datatype issues |

df.describe() | Statistics for numeric columns | Understand distribution & outliers |

Code

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Create a sample DataFrame

data = {'product': ['A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E'],

'sales': [100, 150, np.nan, 200, 50],

'price': [10.0, 15.0, 12.0, 20.0, 5.0]}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print("--- df.head() ---")

print(df.head())

print("\n--- df.info() ---")

df.info()

print("\n--- df.describe() ---")

print(df.describe())

Output

--- df.head() ---

product sales price

0 A 100.0 10.0

1 B 150.0 15.0

2 C NaN 12.0

3 D 200.0 20.0

4 E 50.0 5.0

--- df.info() ---

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 5 entries, 0 to 4

Data columns (total 3 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

0 product 5 non-null object

1 sales 4 non-null float64

2 price 5 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(2), object(1)

memory usage: 248.0+ bytes

--- df.describe() ---

sales price

count 4.000000 5.000000

mean 125.000000 12.400000

std 62.915295 5.176872

min 50.000000 5.000000

25% 87.500000 10.000000

50% 125.000000 12.000000

75% 162.500000 15.000000

max 200.000000 20.000000

✅ 29. Selecting Data

Simple Explanation

df['col']

Selects a single column by name → returns a Series.df.loc[](Label-based)

Uses row/column labels.

The end index IS inclusive.df.iloc[](Integer-based)

Uses row/column positions.

The end index is exclusive.

Code

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'product': ['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'],

'sales': [100, 150, 120, 200],

'price': [10, 15, 12, 20]},

index=['row_one', 'row_two', 'row_three', 'row_four'])

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Direct bracket notation to select the 'sales' column

sales_series = df['sales']

print("\nSelecting 'sales' column with df['sales']:")

print(sales_series)

# .loc to select by label (inclusive)

loc_selection = df.loc['row_one':'row_three', 'product':'sales']

print("\nSelecting with df.loc (label-based):")

print(loc_selection)

# .iloc to select by integer position (exclusive)

iloc_selection = df.iloc[0:2, 2]

print("\nSelecting with df.iloc (integer-based):")

print(iloc_selection)

Output

Original DataFrame:

product sales price

row_one A 100 10

row_two B 150 15

row_three C 120 12

row_four D 200 20

Selecting 'sales' column with df['sales']:

row_one 100

row_two 150

row_three 120

row_four 200

Name: sales, dtype: int64

Selecting with df.loc (label-based):

product sales

row_one A 100

row_two B 150

row_three C 120

Selecting with df.iloc (integer-based):

row_one 10

row_two 15

Name: price, dtype: int64

✅ 30. Setting Index

Simple Explanation

- Use

df.set_index('column')to make a column the new index. - Useful when working with:

- time-series data

- faster row lookups with

.loc

inplace=Truemodifies the DataFrame directly.

Code

import pandas as pd

# Create a DataFrame with a 'date' column

df = pd.DataFrame({

'date': ['2023-01-01', '2023-01-02', '2023-01-03'],

'sales': [200, 250, 180],

'product': ['X', 'Y', 'Z']

})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Set the 'date' column as the new index

df.set_index('date', inplace=True)

print("\nDataFrame after setting 'date' as the index:")

print(df)

Output

Original DataFrame:

date sales product

0 2023-01-01 200 X

1 2023-01-02 250 Y

2 2023-01-03 180 Z

DataFrame after setting 'date' as the index:

sales product

date

2023-01-01 200 X

2023-01-02 250 Y

2023-01-03 180 Z✅ 31. Handling Missing Values

Simple Explanation

- Use

df.isnull()to create a boolean DataFrame where:True→ missing value (NaN)False→ present value

- Then apply

.sum()to count how manyTruevalues each column has. - Since True = 1 and False = 0, the sum gives the number of missing values.

Code

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Create a DataFrame with missing values

data = {'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'David'],

'age': [25, np.nan, 35, 40],

'city': ['New York', 'Los Angeles', np.nan, 'Chicago'],

'sales': [200, 150, 300, np.nan]}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Find the number of missing values in each column

missing_values = df.isnull().sum()

print("\nNumber of missing values in each column:")

print(missing_values)

Output

Original DataFrame:

name age city sales

0 Alice 25.0 New York 200.0

1 Bob NaN Los Angeles 150.0

2 Charlie 35.0 NaN 300.0

3 David 40.0 Chicago NaN

Number of missing values in each column:

name 0

age 1

city 1

sales 1

dtype: int64

✅ 32. Dropping / Filling NaNs

Simple Explanation

df.dropna()- Removes rows (or columns) that contain any missing values.

- Use when missing data is rare and losing a few rows is okay.

df.fillna(value)- Replaces missing values with a specified value.

- Common choices:

- mean for numerical data

- median

- mode for categorical data

- Use when you want to keep all rows and handle missing data logically.

Code

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2, np.nan, 4],

'B': [5, np.nan, np.nan, 8],

'C': [9, 10, 11, 12]})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# --- dropna: remove any rows with missing values ---

df_dropped = df.dropna()

print("\nDataFrame after dropna():")

print(df_dropped)

# --- fillna: replace NaN with the mean of each column ---

df_filled = df.fillna(df.mean())

print("\nDataFrame after fillna(df.mean()):")

print(df_filled)

Output

Original DataFrame:

A B C

0 1.0 5.0 9

1 2.0 NaN 10

2 NaN NaN 11

3 4.0 8.0 12

DataFrame after dropna():

A B C

0 1.0 5.0 9

3 4.0 8.0 12

DataFrame after fillna(df.mean()):

A B C

0 1.0 5.0 9

1 2.0 6.5 10

2 2.5 6.5 11

3 4.0 8.0 12✅ 33. Conditional Replacement

Simple Explanation

- Use boolean indexing with

.locto efficiently replace values based on a condition. - Steps:

- Create a condition, e.g.,

df['inventory'] < 0→ returns a boolean Series. - Use

.loc[condition, 'column']to select only the rows that satisfy the condition. - Assign the new value to those rows.

- Create a condition, e.g.,

Code

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'product': ['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'],

'inventory': [50, -10, 120, -5]})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Replace all negative values in the 'inventory' column with 0

df.loc[df['inventory'] < 0, 'inventory'] = 0

print("\nDataFrame after replacing negative values:")

print(df)

Output

Original DataFrame:

product inventory

0 A 50

1 B -10

2 C 120

3 D -5

DataFrame after replacing negative values:

product inventory

0 A 50

1 B 0

2 C 120

3 D 0

✅ 34. Data Types (Currency to Numeric)

Simple Explanation

To convert a currency string like '$1,200.50' to a numeric type:

- Clean the string: remove

$and,. - Convert to numeric: use

pd.to_numeric()to make it a float.

Code

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'item': ['Laptop', 'Mouse'],

'price': ['$1,200.50', '$25.00']})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

print("\nData types:")

print(df.info())

# 1. Remove '$' and ',' using .str.replace()

df['price_cleaned'] = df['price'].str.replace('$', '').str.replace(',', '')

# 2. Convert cleaned string column to numeric (float)

df['price_numeric'] = pd.to_numeric(df['price_cleaned'])

print("\nDataFrame after conversion:")

print(df[['item', 'price_numeric']])

print("\nNew data types:")

print(df[['item', 'price_numeric']].info())

Output

Original DataFrame:

item price

0 Laptop $1,200.50

1 Mouse $25.00

Data types:

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 2 entries, 0 to 1

Data columns (total 2 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 item 2 non-null object

1 price 2 non-null object

dtypes: object(2)

memory usage: 160.0+ bytes

None

DataFrame after conversion:

item price_numeric

0 Laptop 1200.50

1 Mouse 25.00

New data types:

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 2 entries, 0 to 1

Data columns (total 2 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 item 2 non-null object

1 price_numeric 2 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(1), object(1)

memory usage: 160.0+ bytes

None✅ 35. Removing Duplicates

Simple Explanation

- Use

df.drop_duplicates()to remove duplicate rows. - Parameters:

subset: Specify which columns to consider when identifying duplicates.keep: Decide which duplicate to keep:'first'→ keeps the first occurrence'last'→ keeps the last occurrenceFalse→ removes all duplicates

- Useful for cleaning data where repeated entries are not needed.

Code

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({

'user_id': [1, 2, 1, 3, 2],

'product_id': ['A', 'B', 'A', 'C', 'B'],

'transaction_id': [101, 102, 103, 104, 105]

})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Remove duplicate rows based on 'user_id' and 'product_id'

# Keep the first occurrence of each duplicate

df_unique = df.drop_duplicates(subset=['user_id', 'product_id'], keep='first')

print("\nDataFrame after removing duplicates based on 'user_id' and 'product_id':")

print(df_unique)

Output

Original DataFrame:

user_id product_id transaction_id

0 1 A 101

1 2 B 102

2 1 A 103

3 3 C 104

4 2 B 105

DataFrame after removing duplicates based on 'user_id' and 'product_id':

user_id product_id transaction_id

0 1 A 101

1 2 B 102

3 3 C 104

✅ 36. Applying Functions

Simple Explanation

df.apply(func, axis=…): Applies a function to columns (axis=0) or rows (axis=1). Useful for operations involving multiple columns/rows.series.map(func): Applies a function element-wise to a single column. Great for simple transformations or mapping values.df.applymap(func): Applies a function element-wise to every element in the entire DataFrame. Useful for universal element-wise transformations.

Code

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2, 3], 'B': [4, 5, 6]})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# --- df.apply() example: Sum of columns for each row ---

df['row_sum'] = df.apply(lambda row: row.A + row.B, axis=1)

print("\nAfter df.apply() to get row sum:")

print(df)

# --- series.map() example: Map numbers to words ---

number_map = {1: 'one', 2: 'two', 3: 'three'}

df['A_word'] = df['A'].map(number_map)

print("\nAfter series.map() to convert numbers to words:")

print(df)

# --- df.applymap() example: Convert all numbers to strings ---

df_str = df.applymap(str)

print("\nAfter df.applymap() to convert all elements to strings:")

print(df_str)

Output

Original DataFrame:

A B

0 1 4

1 2 5

2 3 6

After df.apply() to get row sum:

A B row_sum

0 1 4 5

1 2 5 7

2 3 6 9

After series.map() to convert numbers to words:

A B row_sum A_word

0 1 4 5 one

1 2 5 7 two

2 3 6 9 three

After df.applymap() to convert all elements to strings:

A B row_sum A_word

0 1 4 5 one

1 2 5 7 two

2 3 6 9 three

36. Applying Functions

Simple Explanation

df.apply(func, axis=…)- Applies a function across rows (

axis=1) or columns (axis=0). - Useful when a calculation involves multiple columns or rows.

- Applies a function across rows (

series.map(func)- Applies a function element-wise to a single column (Pandas Series).

- Good for simple transformations, e.g., mapping values to words or categories.

df.applymap(func)- Applies a function element-wise to every value in the DataFrame.

- Useful for universal transformations, like converting all numbers to strings.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create a simple DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2, 3], 'B': [4, 5, 6]})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# --- 1. df.apply(): Sum of columns for each row (axis=1) ---

df['row_sum'] = df.apply(lambda row: row.A + row.B, axis=1)

print("\nAfter df.apply() to get row sum:")

print(df)

# --- 2. series.map(): Map numbers to words ---

number_map = {1: 'one', 2: 'two', 3: 'three'}

df['A_word'] = df['A'].map(number_map)

print("\nAfter series.map() to convert numbers to words:")

print(df)

# --- 3. df.applymap(): Convert all elements to strings ---

df_str = df.applymap(str)

print("\nAfter df.applymap() to convert all elements to strings:")

print(df_str)

Output

Original DataFrame:

A B

0 1 4

1 2 5

2 3 6

After df.apply() to get row sum:

A B row_sum

0 1 4 5

1 2 5 7

2 3 6 9

After series.map() to convert numbers to words:

A B row_sum A_word

0 1 4 5 one

1 2 5 7 two

2 3 6 9 three

After df.applymap() to convert all elements to strings:

A B row_sum A_word

0 1 4 5 one

1 2 5 7 two

2 3 6 9 three37. String Methods

Simple Explanation

- Use

.straccessor on a Pandas Series to apply string operations. - You can perform operations like:

.split(),.replace(),.lower(),.upper(),.contains(), etc.

- Example Use Case: Extracting the domain from an email by splitting the string at the ‘@’ symbol.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create a sample DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame({

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob'],

'email': ['alice@example.com', 'bob@work-mail.org']

})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# --- Extract domain from email ---

# Split the email at '@' and take the second part (index 1)

df['domain'] = df['email'].str.split('@').str[1]

print("\nDataFrame after extracting domain:")

print(df)

Output

Original DataFrame:

name email

0 Alice alice@example.com

1 Bob bob@work-mail.org

DataFrame after extracting domain:

name email domain

0 Alice alice@example.com example.com

1 Bob bob@work-mail.org work-mail.org💡 Tip:

The .str accessor is powerful for all kinds of string manipulations in a DataFrame column. You can chain multiple string methods like:

df['domain'].str.upper().str.replace('-', '_')38. GroupBy

Simple Explanation

- GroupBy splits a DataFrame into groups based on some criteria.

- You can apply a function (like

sum,mean,count) to each group independently. - Finally, results are combined into a new data structure (Series or DataFrame).

Steps:

- Split the data into groups (

.groupby()). - Apply an aggregation or transformation (

.sum(),.mean(), etc.). - Combine the results into a new object.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create a sample sales DataFrame

data = {

'region': ['East', 'West', 'East', 'West', 'East', 'West'],

'product': ['A', 'B', 'A', 'C', 'B', 'C'],

'sales': [100, 150, 120, 200, 80, 250]

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# --- Group by 'region' and calculate total sales ---

total_sales_by_region = df.groupby('region')['sales'].sum()

print("\nTotal sales for each region:")

print(total_sales_by_region)

Output

Original DataFrame:

region product sales

0 East A 100

1 West B 150

2 East A 120

3 West C 200

4 East B 80

5 West C 250

Total sales for each region:

region

East 300

West 600

Name: sales, dtype: int64

💡 Tip:

You can also group by multiple columns and use different aggregation functions:

df.groupby(['region', 'product'])['sales'].mean()39. Aggregations (Most Common Product)

Simple Explanation

- When working with grouped data, you often want to know which item appears most frequently in each group.

- Steps:

- Use

.groupby()to group by a column (e.g.,region). - Use

.apply()with a custom function on the grouped column. - Inside the function:

.value_counts()counts occurrences of each unique value..idxmax()returns the value with the highest count.

- Use

Code Example

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({

'region': ['East', 'West', 'East', 'West', 'East', 'West', 'East'],

'product': ['A', 'B', 'A', 'C', 'B', 'C', 'A'] # Product 'A' is most common in East

})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Group by 'region' and find the most frequent product in each group

most_common_product = df.groupby('region')['product'].apply(lambda x: x.value_counts().idxmax())

print("\nMost common product in each region:")

print(most_common_product)

Output

Original DataFrame:

region product

0 East A

1 West B

2 East A

3 West C

4 East B

5 West C

6 East A

Most common product in each region:

region

East A

West C

Name: product, dtype: object

💡 Tip:

- You can also use

.agg()with a lambda for more complex summaries. - For example, to get both most common product and its count:

df.groupby('region')['product'].agg(lambda x: x.value_counts().idxmax())40. Pivot Table

Simple Explanation

- A pivot table reshapes data to summarize it.

- You select:

- Index (rows) → unique values of one column.

- Columns → unique values of another column.

- Values → data to fill in the table.

- You can also specify an aggregation function (

aggfunc) likemean,sum,count.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

data = {'region': ['East', 'West', 'East', 'West', 'East', 'West'],

'product': ['A', 'B', 'A', 'C', 'B', 'C'],

'sales': [100, 150, 120, 200, 80, 250]}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Create a pivot table

pivot = pd.pivot_table(df,

index='region', # Rows

columns='product', # Columns

values='sales', # Values to fill

aggfunc='mean') # Aggregation function

print("\nPivot table of average sales:")

print(pivot)

Output

Original DataFrame:

region product sales

0 East A 100

1 West B 150

2 East A 120

3 West C 200

4 East B 80

5 West C 250

Pivot table of average sales:

product A B C

region

East 110.0 80.0 NaN

West NaN 150.0 225.0

💡 Tip:

NaNmeans no data exists for that combination (e.g., East has no C sales in this example).

41. Melting Data

Simple Explanation

- Melting converts a DataFrame from wide to long format.

- Multiple columns are combined into two columns:

variable→ original column names.value→ values from those columns.

- Useful for plotting or reshaping data for analysis.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Wide format DataFrame

df_wide = pd.DataFrame({

'student': ['Alice', 'Bob'],

'math_score': [90, 85],

'english_score': [95, 80]

})

print("Original WIDE format DataFrame:")

print(df_wide)

# Melt to long format

df_long = pd.melt(df_wide,

id_vars=['student'], # Column to keep

value_vars=['math_score', 'english_score'], # Columns to unpivot

var_name='subject', # Name of new 'variable' column

value_name='score') # Name of new 'value' column

print("\nMelted to LONG format DataFrame:")

print(df_long)

Output

Original WIDE format DataFrame:

student math_score english_score

0 Alice 90 95

1 Bob 85 80

Melted to LONG format DataFrame:

student subject score

0 Alice math_score 90

1 Bob math_score 85

2 Alice english_score 95

3 Bob english_score 80

💡 Tip:

- Melting is the opposite of a pivot table. After melting, you can easily group, aggregate, or plot the long-format data.

42. Merging DataFrames

Simple Explanation

- Merging combines two DataFrames based on a common key column.

- Common join types:

| Join Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Inner | Keeps only rows where the key exists in both DataFrames. |

| Left | Keeps all rows from the left DataFrame and adds matching rows from the right. Non-matches become NaN. |

| Right | Keeps all rows from the right DataFrame and adds matching rows from the left. Non-matches become NaN. |

| Outer | Keeps all rows from both DataFrames. Non-matches on either side become NaN. |

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create two DataFrames

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'id': [1, 2, 3], 'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'id': [2, 3, 4], 'city': ['New York', 'Chicago', 'Houston']})

print("DataFrame 1:")

print(df1)

print("\nDataFrame 2:")

print(df2)

# Inner Join

inner_join = pd.merge(df1, df2, on='id', how='inner')

print("\n--- Inner Join ---")

print(inner_join)

# Left Join

left_join = pd.merge(df1, df2, on='id', how='left')

print("\n--- Left Join ---")

print(left_join)

# Outer Join

outer_join = pd.merge(df1, df2, on='id', how='outer')

print("\n--- Outer Join ---")

print(outer_join)

Output

DataFrame 1:

id name

0 1 Alice

1 2 Bob

2 3 Charlie

DataFrame 2:

id city

0 2 New York

1 3 Chicago

2 4 Houston

--- Inner Join ---

id name city

0 2 Bob New York

1 3 Charlie Chicago

--- Left Join ---

id name city

0 1 Alice NaN

1 2 Bob New York

2 3 Charlie Chicago

--- Outer Join ---

id name city

0 1 Alice NaN

1 2 Bob New York

2 3 Charlie Chicago

3 4 NaN Houston

💡 Tips:

- Always specify the key column (

on='id') for clarity. - Choose the join type depending on whether you want to keep unmatched rows.

Right Joinworks similarly toLeft Joinbut keeps all rows from the right DataFrame.

43. Concatenation

Simple Explanation

Concatenation stacks DataFrames either vertically or horizontally:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Vertical (axis=0) | Stacks DataFrames on top of each other. Columns must match. Indexes may repeat. |

| Horizontal (axis=1) | Stacks DataFrames side by side. Indexes must match. Columns can be different. |

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# DataFrames for vertical stacking

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'A': ['A0', 'A1'], 'B': ['B0', 'B1']})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'A': ['A2', 'A3'], 'B': ['B2', 'B3']})

# DataFrame for horizontal stacking

df3 = pd.DataFrame({'C': ['C0', 'C1'], 'D': ['D0', 'D1']}, index=[0, 1])

print("DataFrame 1:")

print(df1)

print("\nDataFrame 2:")

print(df2)

# --- Vertical Stacking ---

vertical_stack = pd.concat([df1, df2])

print("\n--- Vertically Stacked ---")

print(vertical_stack)

# --- Horizontal Stacking ---

horizontal_stack = pd.concat([df1, df3], axis=1)

print("\n--- Horizontally Stacked ---")

print(horizontal_stack)

Output

DataFrame 1:

A B

0 A0 B0

1 A1 B1

DataFrame 2:

A B

0 A2 B2

1 A3 B3

--- Vertically Stacked ---

A B

0 A0 B0

1 A1 B1

0 A2 B2

1 A3 B3

--- Horizontally Stacked ---

A B C D

0 A0 B0 C0 D0

1 A1 B1 C1 D1

💡 Tips:

- For vertical stacking, mismatched columns will create

NaNfor missing columns. - For horizontal stacking, mismatched indexes will create

NaNfor missing rows. pd.concatis very flexible; you can also useignore_index=Trueto reindex vertically stacked DataFrames.

44. Cross Tabulation

Simple Explanation

pd.crosstab() creates a frequency table that counts how often combinations of two (or more) categorical variables occur. It’s very useful for understanding relationships between categories.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({

'Gender': ['Male', 'Female', 'Female', 'Male', 'Male', 'Female'],

'Preference': ['A', 'B', 'A', 'A', 'B', 'B']

})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Create a frequency table of Gender vs. Preference

cross_tab = pd.crosstab(df['Gender'], df['Preference'])

print("\nCross-tabulation (Frequency Table):")

print(cross_tab)

Output

Original DataFrame:

Gender Preference

0 Male A

1 Female B

2 Female A

3 Male A

4 Male B

5 Female B

Cross-tabulation (Frequency Table):

Preference A B

Gender

Female 1 2

Male 2 1

Tips

- You can add

margins=Trueto see row and column totals:

pd.crosstab(df['Gender'], df['Preference'], margins=True)Works with more than 2 variables by passing multiple Series.

You can apply aggregation with the values and aggfunc parameters if counting numeric data instead of just frequency.

45. Datetime Conversion

Simple Explanation

To work effectively with dates in Pandas, you need to convert date strings to datetime objects. This allows for easy comparison, filtering, and time-based operations.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create a DataFrame with a date column as strings

df = pd.DataFrame({

'date': ['2023-10-27', '2023-10-28', '2023-10-29'],

'sales': [200, 250, 180]

})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

print("\nData type of 'date' column:", df['date'].dtype)

# Convert the 'date' column to datetime objects

df['date'] = pd.to_datetime(df['date'])

print("\nDataFrame after conversion:")

print(df)

print("\nNew data type of 'date' column:", df['date'].dtype)

Output

Original DataFrame:

date sales

0 2023-10-27 200

1 2023-10-28 250

2 2023-10-29 180

Data type of 'date' column: object

DataFrame after conversion:

date sales

0 2023-10-27 200

1 2023-10-28 250

2 2023-10-29 180

New data type of 'date' column: datetime64[ns]

46. Time-based Filtering

Simple Explanation

Once the date column is converted and set as the index, you can filter by year, month, or date range using string-based indexing. This is extremely useful for time series data analysis.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create a DataFrame with a DatetimeIndex

date_rng = pd.date_range(start='2022-01-01', end='2023-10-30', freq='D')

df = pd.DataFrame(date_rng, columns=['date'])

df['data'] = range(len(df))

df.set_index('date', inplace=True)

print("Original DataFrame (head):")

print(df.head())

# Select all data from the year 2022

data_2022 = df['2022']

print("\nData from the year 2022 (head):")

print(data_2022.head())

# Select data from a specific month

data_jan_2022 = df['2022-01']

print("\nData from January 2022 (head):")

print(data_jan_2022.head())

Output

Original DataFrame (head):

data

date

2022-01-01 0

2022-01-02 1

2022-01-03 2

2022-01-04 3

2022-01-05 4

Data from the year 2022 (head):

data

date

2022-01-01 0

2022-01-02 1

2022-01-03 2

2022-01-04 3

2022-01-05 4

Data from January 2022 (head):

data

date

2022-01-01 0

2022-01-02 1

2022-01-03 2

2022-01-04 3

2022-01-05 4

Tips

- After conversion, you can easily extract parts of the date:

df['year'] = df.index.year

df['month'] = df.index.month

df['day'] = df.index.day

- Combine filtering with conditions:

df['2022-03':'2022-06'] # Data from March to June 202247. Resampling

Simple Explanation

Resampling is used to change the frequency of time series data:

- Downsampling: Reduce the frequency (e.g., daily → monthly) by aggregating values (

mean,sum,max, etc.). - Upsampling: Increase the frequency (e.g., monthly → daily) by filling or interpolating missing values.

The .resample() method is used on a DatetimeIndex and requires an aggregation function for downsampling.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Create a DataFrame with daily stock prices

date_rng = pd.date_range(start='2023-01-01', periods=90, freq='D')

df_daily = pd.DataFrame(date_rng, columns=['date'])

df_daily['price'] = np.random.randint(100, 150, size=len(date_rng))

df_daily.set_index('date', inplace=True)

print("Original daily data (head):")

print(df_daily.head())

# Downsample daily data to monthly average price

df_monthly = df_daily['price'].resample('M').mean()

print("\nResampled monthly average price:")

print(df_monthly)

Output Example

Original daily data (head):

price

date

2023-01-01 106

2023-01-02 129

2023-01-03 108

2023-01-04 112

2023-01-05 119

Resampled monthly average price:

date

2023-01-31 124.03

2023-02-28 126.61

2023-03-31 124.64

Name: price, dtype: float64

Tips

- Common frequency codes for

.resample():'D'→ Daily'W'→ Weekly'M'→ Month-end'Q'→ Quarter-end'Y'→ Year-end

- Example of upsampling with forward fill:

df_monthly_upsampled = df_monthly.resample('D').ffill()

- You can combine

.resample()with any aggregation function:

df_daily['price'].resample('W').max() # Weekly maximum48. Rolling Windows

Simple Explanation

A rolling window performs calculations over a fixed-size “window” of consecutive data points that moves across the time series:

- Each window contains a subset of consecutive rows.

- Common uses: moving averages, rolling sums, min/max, standard deviation, etc.

- Example: a 7-day rolling average calculates the average of the current day plus the previous 6 days, then slides forward one day and repeats.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Daily sales data

df = pd.DataFrame({

'date': pd.date_range(start='2023-01-01', periods=15, freq='D'),

'sales': [10, 20, 15, 30, 25, 40, 35, 50, 45, 60, 55, 70, 65, 80, 75]

})

df.set_index('date', inplace=True)

print("Original daily sales:")

print(df)

# Calculate a 7-day rolling average

df['7_day_rolling_avg'] = df['sales'].rolling(window=7).mean()

print("\nDataFrame with 7-day rolling average:")

print(df)

Output Example

Original daily sales:

sales

date

2023-01-01 10

2023-01-02 20

2023-01-03 15

2023-01-04 30

2023-01-05 25

2023-01-06 40

2023-01-07 35

2023-01-08 50

2023-01-09 45

2023-01-10 60

2023-01-11 55

2023-01-12 70

2023-01-13 65

2023-01-14 80

2023-01-15 75

DataFrame with 7-day rolling average:

sales 7_day_rolling_avg

date

2023-01-01 10 NaN

2023-01-02 20 NaN

2023-01-03 15 NaN

2023-01-04 30 NaN

2023-01-05 25 NaN

2023-01-06 40 NaN

2023-01-07 35 25.0

2023-01-08 50 30.0

2023-01-09 45 35.0

2023-01-10 60 40.0

2023-01-11 55 45.0

2023-01-12 70 50.0

2023-01-13 65 55.0

2023-01-14 80 60.0

2023-01-15 75 65.0

Tips

- Window size determines how many rows are included in the calculation.

- The first few rows will often be NaN because the window isn’t full yet.

- You can compute other functions like:

df['7_day_rolling_sum'] = df['sales'].rolling(window=7).sum()

df['7_day_rolling_std'] = df['sales'].rolling(window=7).std()

- Works well for smoothing noisy time series data.

49. Time Deltas

Simple Explanation

A Time Delta represents the difference between two dates or times. In Pandas:

- Subtracting two datetime columns gives a Timedelta Series.

- You can extract useful information such as:

.dt.days→ total days.dt.seconds→ total seconds.dt.total_seconds()→ total duration in seconds

This is very useful for calculating durations, age, or elapsed time between events.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

# Create a DataFrame with two datetime columns

df = pd.DataFrame({

'start_date': pd.to_datetime(['2023-01-01', '2023-02-15', '2023-03-20']),

'end_date': pd.to_datetime(['2023-01-10', '2023-03-01', '2023-04-01'])

})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Calculate time difference

df['time_delta'] = df['end_date'] - df['start_date']

# Extract difference in days

df['days_difference'] = df['time_delta'].dt.days

print("\nDataFrame with time difference in days:")

print(df)

Output Example

Original DataFrame:

start_date end_date

0 2023-01-01 2023-01-10

1 2023-02-15 2023-03-01

2 2023-03-20 2023-04-01

DataFrame with time difference in days:

start_date end_date time_delta days_difference

0 2023-01-01 2023-01-10 9 days 9

1 2023-02-15 2023-03-01 14 days 14

2 2023-03-20 2023-04-01 12 days 12

Tips

Timedeltacan also be used for arithmetic with dates, e.g., adding/subtracting days:

df['new_date'] = df['start_date'] + pd.Timedelta(days=7)

- Works with hours, minutes, seconds, e.g.,

pd.Timedelta(hours=5). - Ideal for time-based calculations like calculating SLA, age, or subscription durations.

50. Matplotlib Basics (Line Plot)

Simple Explanation

- Line plots visualize trends over a continuous variable (like time).

- Steps:

- Import

matplotlib.pyplot. - Prepare

xandydata. - Use

plt.plot(x, y). - Add labels, title, and show the plot.

- Import

Code Example

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Sample data

years = [2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022]

sales = [15000, 18000, 16000, 22000, 27000]

# Line plot

plt.plot(years, sales)

# Add title and labels

plt.title("Yearly Sales")

plt.xlabel("Year")

plt.ylabel("Sales ($)")

# Display

plt.show()

Output:

A line chart showing sales trends over years with proper labels.

51. Scatter Plot

Simple Explanation

- Scatter plots visualize the relationship or correlation between two numerical variables.

- Use

plt.scatter(x, y).

Code Example

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Sample data

age = [25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60]

income = [40000, 55000, 60000, 75000, 90000, 110000, 95000, 120000]

# Scatter plot

plt.scatter(age, income)

# Add title and labels

plt.title("Age vs. Income")

plt.xlabel("Age")

plt.ylabel("Annual Income ($)")

# Display

plt.show()

Output:

A scatter plot showing the relationship between age and income (generally positive correlation).

52. Histogram

Simple Explanation

- Histograms show the distribution of a single numerical variable.

- Use

plt.hist(data, bins=number_of_bins)to control granularity.

Code Example

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Sample data: ages of 100 customers

customer_age = np.random.randint(18, 70, size=100)

# Histogram

plt.hist(customer_age, bins=10, edgecolor='black')

# Add title and labels

plt.title("Distribution of Customer Age")

plt.xlabel("Age")

plt.ylabel("Number of Customers")

# Display

plt.show()

Output:

Histogram showing how customer ages are distributed across 10 bins.

53. Seaborn vs. Matplotlib

Simple Explanation

- Matplotlib: Foundational plotting library. Very flexible, but can require a lot of code for polished plots.

- Seaborn: Built on top of Matplotlib. Simplifies statistical visualization and improves aesthetics.

Key Advantages of Seaborn

- Better Aesthetics: Beautiful default styles.

- Works with DataFrames: Directly use column names from a DataFrame.

sns.scatterplot(x='col1', y='col2', data=df) - Complex Plots Made Easy: Box plots, violin plots, heatmaps, pair plots, etc., are simpler to create than with Matplotlib alone.

54. Box Plot

Simple Explanation

- Box plots show the distribution of a numerical variable across categories.

- Displays median, quartiles, and outliers.

- Seaborn makes it simple with

sns.boxplot().

Code Example

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

# Sample data

data = {'department': ['HR', 'IT', 'Sales', 'HR', 'IT', 'Sales', 'HR', 'IT', 'Sales'],

'salary': [60000, 90000, 75000, 65000, 110000, 120000, 62000, 95000, 80000]}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Create the box plot

sns.boxplot(x='department', y='salary', data=df)

# Add title

plt.title("Salary Distribution by Department")

# Display

plt.show()

Output:

Three boxes (one per department) showing median, quartiles, and outliers.

55. Heatmap

Simple Explanation

- A heatmap visualizes values in a matrix using colors.

- Often used for correlation matrices.

- Use

df.corr()to compute correlations, thensns.heatmap()to visualize.

Code Example

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

# Sample data

df = pd.DataFrame({'age': [25, 30, 35, 40],

'income': [50000, 60000, 75000, 90000],

'score': [85, 88, 92, 95]})

# Compute correlation matrix

correlation_matrix = df.corr()

# Create heatmap

sns.heatmap(correlation_matrix, annot=True, cmap='coolwarm')

# Add title

plt.title("Correlation Matrix Heatmap")

# Display

plt.show()

Output:

A 3×3 heatmap showing correlations, with values annotated in each cell and color-coded.

56. Subplots

Simple Explanation

plt.subplots()lets you create multiple plots in a single figure.- Returns a figure object (

fig) and axes object(s) (ax) for plotting individually. - Use ax[i] to access a specific subplot.

figsizecontrols the overall figure size.plt.tight_layout()prevents overlapping elements.

Code Example

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Sample data

years = [2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022]

sales = [150, 180, 160, 220, 270]

profit = [20, 35, 15, 50, 65]

# Create a figure with 1 row and 2 columns of subplots

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Plot on the first subplot

ax[0].plot(years, sales)

ax[0].set_title('Yearly Sales')

ax[0].set_xlabel('Year')

ax[0].set_ylabel('Sales ($)')

# Plot on the second subplot

ax[1].bar(years, profit, color='green')

ax[1].set_title('Yearly Profit')

ax[1].set_xlabel('Year')

ax[1].set_ylabel('Profit ($)')

# Adjust layout and display

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Output:

A single figure with two plots side-by-side:

- Left: line plot for sales

- Right: bar chart for profit

57. Customization

Simple Explanation

- Add titles and axis labels using:

plt.title()→ plot titleplt.xlabel()→ x-axis labelplt.ylabel()→ y-axis label

- You can also change colors, markers, line styles, and fonts for further customization.

Code Example

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Sample data

x = [1, 2, 3, 4]

y = [10, 20, 25, 30]

plt.plot(x, y, marker='o', linestyle='--', color='orange')

# Add title and labels

plt.title("My Simple Plot")

plt.xlabel("X-axis Label")

plt.ylabel("Y-axis Label")

# Display the plot

plt.show()

Output:

A line plot with a title, labeled axes, and custom markers and line style.

58. Saving Plots

Simple Explanation

- After creating a Matplotlib plot, save it to a file using

plt.savefig(). - Call

plt.savefig()beforeplt.show(). - File format is determined by the extension:

.png,.pdf,.svg, etc.

Code Example

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = [1, 2, 3, 4]

y = [10, 20, 25, 30]

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.title("Plot to be Saved")

# Save the figure

plt.savefig("my_plot.png") # PNG file

# plt.savefig("my_plot.pdf") # PDF file

plt.show()

Output:

- The plot is displayed.

- A file

my_plot.pngis created in the current directory.

59. Interactive Plots

Simple Explanation

- Interactive plots allow hovering, zooming, panning, and selection, which is great for dashboards or web apps.

- Use libraries like Plotly for interactive charts.

- Static plots (Matplotlib/Seaborn) are better for reports, while interactive ones are for user exploration.

Example Scenarios:

- Hover over a stock price line to see exact values.

- Zoom into a one-month period in a time series.

- Compare multiple categories dynamically.

60. Categorical Plot (Count Plot)

Simple Explanation

- Count plots are like histograms for categorical variables.

- Shows how many times each category appears in your data.

- Use Seaborn’s

sns.countplot().

Code Example

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

# Sample data

data = {'product_type': ['Electronics', 'Clothing', 'Books', 'Electronics', 'Clothing', 'Electronics']}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Create count plot

sns.countplot(x='product_type', data=df)

plt.title("Frequency of Product Types")

plt.show()

Output:

- Bar chart showing:

- Electronics → 3

- Clothing → 2

- Books → 1

61. Train-Test Split

Simple Explanation

- The goal is to split your dataset into two parts:

- Training set: Used to train your model.

- Testing set: Used to evaluate the model on unseen data.

- This prevents overfitting and checks if your model generalizes well.

test_sizecontrols the fraction of data for testing.random_stateensures reproducibility.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Sample features (X) and target (y)

X = pd.DataFrame({

'age': [25, 30, 35, 40, 45],

'salary': [50000, 60000, 75000, 90000, 110000]

})

y = pd.Series([0, 0, 1, 1, 1]) # 0: No Purchase, 1: Purchase

# Split into training (80%) and testing (20%)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

print("Shapes:")

print(f"X_train: {X_train.shape}, X_test: {X_test.shape}")

print(f"y_train: {y_train.shape}, y_test: {y_test.shape}")

print("\nX_train:")

print(X_train)

Output Example

Original Features (X):

age salary

0 25 50000

1 30 60000

2 35 75000

3 40 90000

4 45 110000

Original Target (y):

0 0

1 0

2 1

3 1

4 1

dtype: int64

Shapes:

X_train: (4, 2), X_test: (1, 2)

y_train: (4,), y_test: (1,)

X_train:

age salary

4 45 110000

2 35 75000

0 25 50000

3 40 90000

✅ Key Points

train_test_split()shuffles the data by default.test_size=0.2→ 20% of data is used for testing.random_state=42ensures the split is the same every time.- Training set is used to fit the model, testing set to evaluate performance.

62. Feature Scaling

Simple Explanation

- Feature scaling ensures that numerical variables are on the same scale, which improves performance for many machine learning algorithms.

- Two common scalers:

- StandardScaler

- Rescales data to have mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1.

- Useful for algorithms that assume normal distribution (e.g., Linear Regression, SVM, Logistic Regression).

- MinMaxScaler

- Rescales data to a fixed range, usually [0, 1].

- Useful for algorithms sensitive to magnitude (e.g., Neural Networks) or when preserving sparsity is important.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler

# Sample data with features on different scales

data = {'age': [25, 30, 35, 40], 'income': [50000, 60000, 75000, 90000]}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print("Original Data:")

print(df)

# --- StandardScaler ---

scaler_standard = StandardScaler()

df_standardized = pd.DataFrame(scaler_standard.fit_transform(df), columns=df.columns)

print("\nAfter StandardScaler (mean=0, std=1):")

print(df_standardized)

# --- MinMaxScaler ---

scaler_minmax = MinMaxScaler()

df_normalized = pd.DataFrame(scaler_minmax.fit_transform(df), columns=df.columns)

print("\nAfter MinMaxScaler (range=[0, 1]):")

print(df_normalized)

Output

Original Data:

age income

0 25 50000

1 30 60000

2 35 75000

3 40 90000

After StandardScaler (mean=0, std=1):

age income

0 -1.341641 -1.269269

1 -0.447214 -0.423090

2 0.447214 0.564120

3 1.341641 1.128239

After MinMaxScaler (range=[0, 1]):

age income

0 0.0 0.000000

1 0.3 0.285714

2 0.6 0.714286

3 1.0 1.000000

✅ Key Points

- Scaling helps models converge faster and improves accuracy.

- Always fit the scaler on the training set and then transform both training and testing sets to avoid data leakage.

- StandardScaler is good when data has outliers; MinMaxScaler keeps data in a specific range.

63. Encoding Categorical Variables

Simple Explanation

- Many machine learning algorithms can only handle numerical input.

- One-Hot Encoding converts a categorical column into multiple binary columns, one for each category.

- Example: For a

citycolumn with values'New York','London','Paris':- New columns created:

city_New York,city_London,city_Paris - Each row gets a 1 in the column corresponding to its category and 0 elsewhere.

- New columns created:

Code Example

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

# Sample DataFrame with a categorical feature

df = pd.DataFrame({'city': ['New York', 'London', 'New York', 'Paris', 'London']})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Initialize OneHotEncoder

# sparse_output=False makes the output a dense NumPy array

encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse_output=False)

# Fit and transform the data

onehot_encoded = encoder.fit_transform(df[['city']])

# Create a new DataFrame with the encoded columns

encoded_df = pd.DataFrame(onehot_encoded, columns=encoder.get_feature_names_out(['city']))

print("\nOne-Hot Encoded DataFrame:")

print(encoded_df)

Output

Original DataFrame:

city

0 New York

1 London

2 New York

3 Paris

4 London

One-Hot Encoded DataFrame:

city_London city_New York city_Paris

0 0.0 1.0 0.0

1 1.0 0.0 0.0

2 0.0 1.0 0.0

3 0.0 0.0 1.0

4 1.0 0.0 0.0

✅ Key Points

- Each categorical value is now represented numerically without imposing any order.

- One-Hot Encoding is ideal for nominal variables (no natural order).

- For ordinal variables (like

'Low' < 'Medium' < 'High'), use Label Encoding instead.

64. Label Encoding

Simple Explanation

- Label Encoding converts each category in a column into a unique integer.

- Example:

sizecolumn with values'S','M','L'might be encoded as:'L'→ 0'M'→ 1'S'→ 2

- Best for ordinal features where there is a natural order.

- Not recommended for nominal features (like city names), because numbers imply a ranking that does not exist.

Code Example

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

# Sample DataFrame with an ordinal feature

df = pd.DataFrame({'size': ['S', 'M', 'L', 'S', 'M']})

print("Original DataFrame:")

print(df)

# Initialize LabelEncoder

encoder = LabelEncoder()

# Fit and transform the 'size' column

df['size_encoded'] = encoder.fit_transform(df['size'])

print("\nDataFrame after Label Encoding:")

print(df)

# Show mapping of categories to numbers

print("\nMapping of categories to numbers:")

print(dict(zip(encoder.classes_, encoder.transform(encoder.classes_))))

Output

Original DataFrame:

size

0 S

1 M

2 L

3 S

4 M

DataFrame after Label Encoding:

size size_encoded

0 S 2

1 M 1

2 L 0

3 S 2

4 M 1

Mapping of categories to numbers: